CHIATURA CABLE CARS [GE]

Exploration #155 Chiatura cable cars (testo italiano a fondo pagina). Chiatura cable cars were a network of cable cars built so that almost every corner of the mining town was accessible. Chiatura (ჭიათურა) is a Georgian municipality located in a narrow mountain valley on the banks of the Qvirila River. In 1879 large deposits of manganese were discovered in that valley and the state started the JSC Chiaturmanganese company to manage its exploitation. As early as 1905, a small town was built for the extraction of the metal and a railway link was set up to transport the ore to the Zestaponi ferroalloy plant, which is still in operation today, although it is in such a poor state of repair that walking past it could be mistaken for a disused industry.

Over the years, manganese production rose to 60% of the world’s total production, as did the number of miners employed, estimated at over 4000.

The employees worked 18 hours a day sleeping in the mines, always covered in soot, without even a toilet. The problem was also due to the logistical difficulties of moving around, as the mines were located along the valley, with access on the steep, steep slopes.

The first workers’ movements arose, led by a young Stalin, here renamed with the battle name of “Koba”, who left his mark in Chiatura, winning it over with his oratory to the cause of the Bolsheviks, the only town in a Menshevik area.

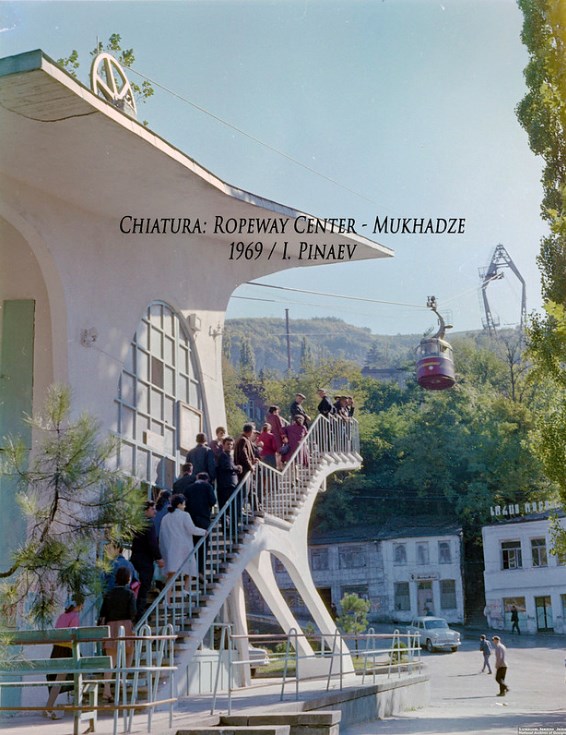

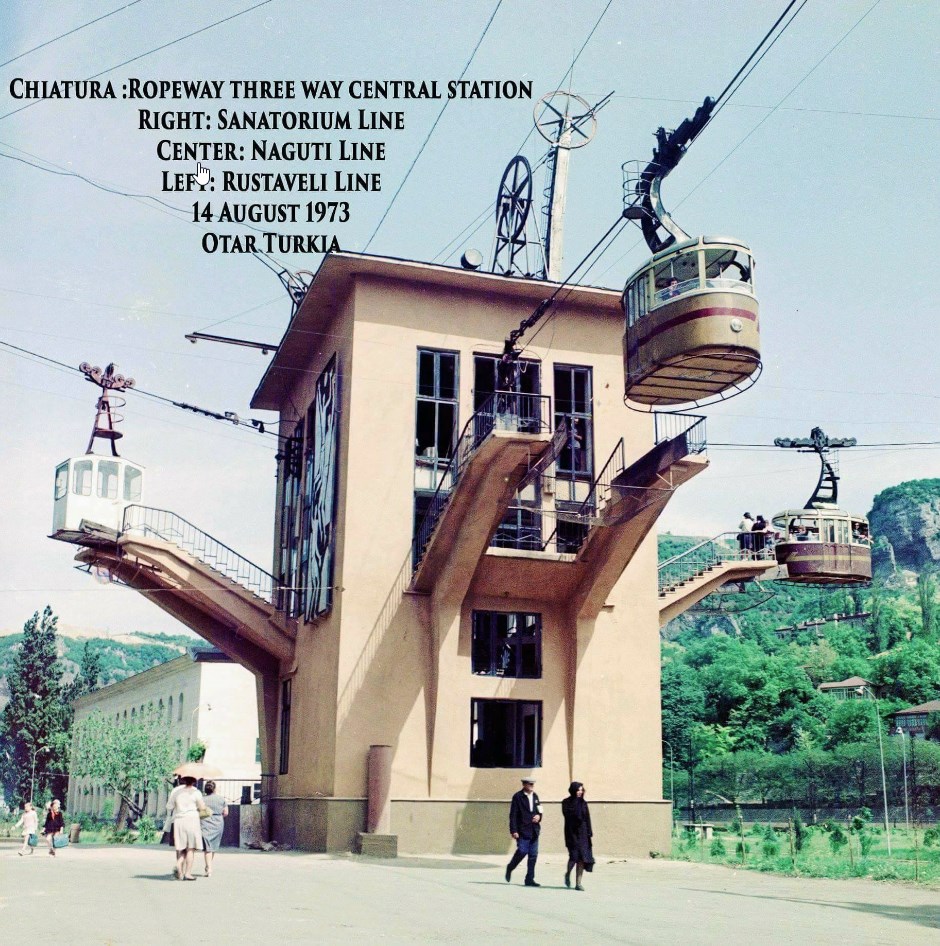

In June-July 1913 the miners went on strike for 55 days, demanding an eight-hour day, higher wages and no more night work. Working conditions improved but the problems of travel were only solved a few years later when, after the annexation of Georgia to Russia, Russian engineers decided that the best solution for transport was by air.

A network of cable cars was built so that almost every corner of the mining town was accessible. The system transported workers from their homes in the lower part of the valley to the mines that dotted the mountains. The system was also used to transport manganese to the various factories in the area. What merits Sergeant Major ‘Koba’ had in the project remains to be seen, but the cable car system was at the time one of the most fascinating engineering feats on the planet. As many as 21 pairs of cabins were built, climbing a total length of over 6,000 metres. Of these, 15 remained in service virtually unchanged for 50 years until the beginning of 2019 when they were stopped with the promise of building new, more modern ones.

The promise was not kept, however, and today the miners of Chiatura, which has become the “ghost town of abandoned cable cars”, find themselves without their precious means of transport, with the result that they have to rely once again on old, slow little minibuses that climb the winding mountain roads.

Of the 15 cable cars that stopped some have been dismantled, of others only the departure and arrival station remains, while some rest intact and left without maintenance a few metres from their station, probably to avoid being stolen, waiting for a restart that will never happen again or for an unlikely restoration.

Esplorazione #155. Chiatura (ჭიათურა) è un comune georgiano che si trova in una stretta valle di montagna, sulle rive del fiume Qvirila. Nel 1879 vennero scoperti ampi depositi di manganese in quella valle e lo stato avviò la società JSC Chiaturmanganese per gestirne lo sfruttamento. Già nel 1905 era sorta una piccola città funzionale all’estrazione del metallo e un collegamento ferroviario per trasportare i minerali all’impianto di ferroleghe di Zestaponi, tutt’oggi attivo, anche se talmente mal tenuto che passandoci accanto si potrebbe scambiare per un industria in disuso.

Negli anni la produzione di manganese è salita fino a raggiungere il 60% della produzione totale mondiale, così come il numero di minatori impegnati, che si stima siamo arrivati a più di 4000.

Gli impiegati lavoravano 18 ore al giorno dormendo nelle miniere, sempre coperti di fuliggine, senza neanche un bagno. Il problema era anche da imputare alle difficoltà logistiche degli spostamenti, poiché le miniere erano dislocate lungo la valle, con gli accessi sui ripidi e scoscesi pendii.

Sorsero quindi i primi movimenti operai, guidati da un giovane Stalin, qui ribattezzato col nome di battaglia di “Koba”, che proprio a Chiatura lasciò il segno conquistandola con la sua oratoria alla causa dei Bolscevichi, unica città in un’area menscevica.

Nel giugno-luglio 1913 i minatori scioperarono 55 giorni, chiedendo una giornata di 8 ore, salari più alti e niente più lavoro notturno. Le condizioni di lavoro migliorarono ma i problemi di spostamento furono risolti solo alcuni anni dopo quando, dopo l’annessione della Georgia alla Russia, gli ingegneri russi decisero che la soluzione migliore per il trasporto era quella aerea.

Fu quindi costruita una rete di funivie in modo che quasi ogni angolo della città mineraria fosse accessibile. Il sistema trasportava i lavoratori dalle loro case nella parte inferiore della valle alle miniere che punteggiavano le montagne. Il sistema era anche usato per trasportare il manganese nelle varie fabbriche della zona. Quali siano stati i meriti del sergente maggiore “Koba” nel progetto resta tutto da verificare, ma il sistema di funivie era l’epoca una delle opere ingegneristiche più affascinanti del pianeta.

Furono costruite ben 21 coppie di cabine che si inerpicavano per un’estensione complessiva di oltre 6mila metri. Di queste 15 sono rimaste in servizio pressoché identiche rispetto a 50 anni fino all’inizio del 2019 quando sono state fermate con la promessa di costruirne nuove e più moderne.

La promessa non è stata tuttavia mantenuta e ad oggi i minatori di Chiatura, divenuta la “città fantasma delle funivie abbandonate”, si ritrovano senza il loro prezioso mezzo di trasporto con la conseguenza di riaffidarsi a vecchi e lenti piccoli pulmini che si inerpicano per tortuose stradine di montagna.

Delle 15 funivie fermate alcune sono state smantellate, di altre rimane solo la stazione di partenza e arrivo, mentre alcune riposano integre e lasciate senza manutenzione a pochi metri dalla loro stazione, probabilmente per evitare di essere rubate, in attesa di una ripartenza che non avverrà più o di improbabile restauro.